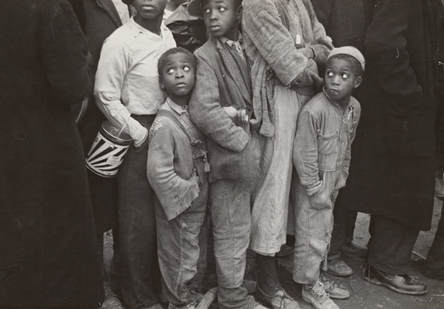

"Flood refugees at mealtime, Forrest City, Arkansas," 1937. Photo by Walker Evans. From The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Flood refugees at mealtime, Forrest City, Arkansas," 1937. Photo by Walker Evans. From The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. Empathy, like civility, seems to be a vanishing American quality. The ability to imagine oneself in another person’s situation and understand that person’s feelings typically engenders compassion and a sense of shared human experience. Without empathy, we tend to align ourselves with others whose experiences we can identify with. That results in homogenized communities and a bubbling fear of those who are different—the threat of “The Other,” as described so vividly in Ryszard Kapuściński’s book that borrows that title. That’s where our nation—and much of the world—finds itself right now. Bill Bishop, formerly a columnist with the Lexington Herald-Leader, relied on demographic data to sound the alarm about this phenomenon in his 2009 book The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart. He argued that our choosing to live in neighborhoods with others who share our lifestyle and our beliefs has helped create the political and cultural polarization we see today. Unfortunately we currently have political leaders who find stoking those fears useful for holding on to their power. By promulgating misleading data and straight-up lies, they are able to prey on people’s fears of those who are different—or simply unfamiliar—and push agendas that lack compassion and humanity. Our nation has a long history of persecuting immigrants and those whom we perceive to be different. We have been callous, hateful, distrustful, even cruel—all while pointing smugly to the Statue of Liberty, our national symbol of compassion. It is our responsibility as citizens to distinguish the facts from the untruths and to consider the effect of proposed policy on all people, not just those who look and think like we do. So how do we build empathy for others who live very different lives from our own? If you live or work among a diverse population of people, it’s much easier. You interact with people with different backgrounds from yours every day. So talk to them. Get to know them. Ask them questions. Share a meal. I expect you’ll find you’re not very different after all. If you live and work in an area with little diversity, as I do, you have to work a little harder to discover the empathy and compassion necessary for a united nation truly interested in justice for all. You can volunteer to work with groups of people whose life experiences are different from yours. If you have the means, you can travel. You can take classes or attend public lectures. But perhaps one of the simplest ways to develop empathy is to read. Read widely. Read everything you can get your hands on. Read books by authors from other countries. Read history so you’ll know the struggles of those who preceded us. Read biographies about people you’ve never heard of. And read fiction. Good fiction invites you into a world you know nothing about and engages your emotions in a way that encourages you to feel empathy for the characters. Whatever their situation—however different from anything you’ve ever known—you begin to identify with the fictional characters: you feel their pain, their sorrow, their happiness, their embarrassment, their fear. You struggle with their decisions. You want them to succeed. You live their lives vicariously. If reading fiction is not a regular part of your life, here are a few suggestions to get you started. Of course, there are hundreds of others to choose from. Feel free to share a comment below listing other books readers might find compelling.

In the second Appendix of The Last Resort, Pud lists what he is reading while working as a researcher at Harvard Forest. The almost wacky list includes a historical thriller, a collection of essays by the humorist James Thurber, a contemporary novel, a telling of Maurice Herzog’s trek up Annapurna, and a book of Ozark folk tales. He was also rereading Thoreau’s Walden and working his way through Ridpath’s history. In 1953, Pud and Mary Marrs had no television. Reading was their primary pastime. I suspect that in that era more people read more widely. With the widespread establishment of public libraries and the advent of paperbacks, books became more accessible. Newspapers were commonly found in homes. Magazines were popular. But in the digital age, we read “soundbites.” We rarely dig deeply into a story or analysis. Fewer still pick up a book or download a novel to an electronic device. Who has time for that? As we once again consider important policy and legislation relating to immigrants, refugees, foreign aid, and how we respond to national disasters that disproportionately affect the poor and marginalized, let us all summon as much empathy and compassion for our fellow travelers as we possibly can. Let’s all pick up a good book and read. And then let’s make our voices heard. For another call to action, please read the comment left by Vince Fallis at the bottom of Tragic Patterns.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed