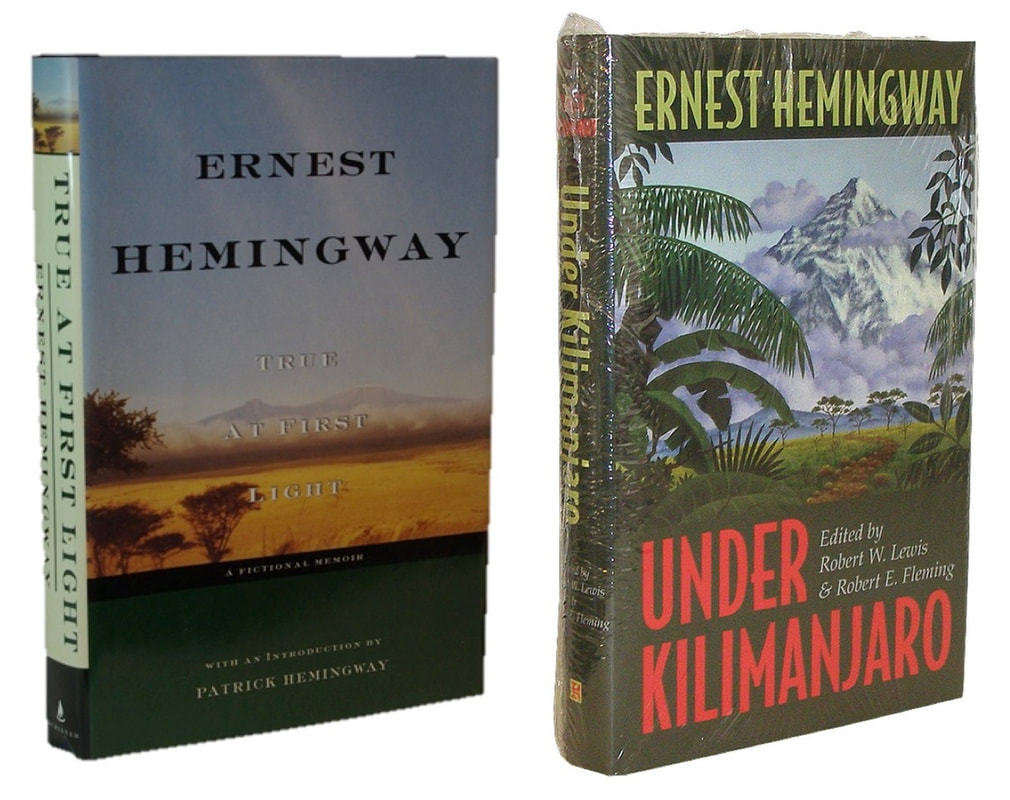

Mary and Ernest Hemingway in Kenya during his second African safari (1953). Mary and Ernest Hemingway in Kenya during his second African safari (1953). David Hoefer, of Louisville, Ky., is co-editor of The Last Resort and the author of the book's Introduction. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. It will surprise few readers to learn that editing a previously unpublished manuscript is not unlike wading waist-deep into an endless stream of choices. At least that’s what Sallie and I found in preparing Pud Goodlett’s 1940s Salt River journal for publication as The Last Resort. We felt a moral obligation to reproduce the author’s original text as faithfully as possible, but other considerations managed to creep in. Some of them were practical—for example, pencil smudges and strikethroughs in the source document required interpretive skill. There were also, on occasion, plausible arguments for more extensive revision. Does one correct spelling errors? Pick grammatical nits? What about gray areas like replacing period slang or clunky phrasing with something easier to read (after all, Pud was only 19 when he started his journal)? Aren’t editors supposed to edit? Sallie and I erred on the side of laissez faire et laissez passer—let do and let pass—but not everyone follows the same strategy. An interesting counterexample involves an unpublished manuscript by the patron saint of outdoor writers, Ernest Hemingway. Though he’s often associated with big-game hunting in Africa, Hemingway undertook only two safaris during his lifetime. The first occurred in 1933 and resulted in Green Hills of Africa, published two years later and viewed by some as the gold standard for this genre of writing. The second took place in the early 1950s and generated an unfinished 850-page manuscript, partly handwritten and partly typed, deposited by Hemingway for safekeeping in a Cuban bank vault. Since Hemingway’s death in 1961, “the African book” (as he called it) has been published not once but twice in two very different versions. The first, appearing in 1999 and given the name True at First Light, was heavily edited by Hemingway’s son, Patrick. It was, after a fashion, a father-and-son collaboration. The same manuscript served as the source for a second publication, Under Kilimanjaro, in 2005, edited by a pair of Hemingway scholars, Robert W. Lewis and Robert E. Fleming. They took the opposite approach, leaving the original manuscript largely intact. According to Lewis and Fleming, “[T]his book deserves as complete and faithful a publication as possible without editorial distortion, speculation, or textually unsupported attempts at improvement.” Sallie’s and my approach was more Kilimanjaro than First Light, which isn’t to say that we didn’t earn our paycheck as editors (speaking figuratively here, as there’s no money in scholarly self-publication). The appendices of World War II correspondence and the Harvard Forest journal were created after a meticulous review of the source documents and an appropriate reduction in size and scope. The introduction, annotations, taxonomic list, and other content additions involved considerable time and required input from both of us. But the point of the book—Pud’s delightful journal of halcyon days on Salt River—is as verbatim as we could make it. The Last Resort is the authentic work of an authentic voice before our current period of largesse and decline.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed