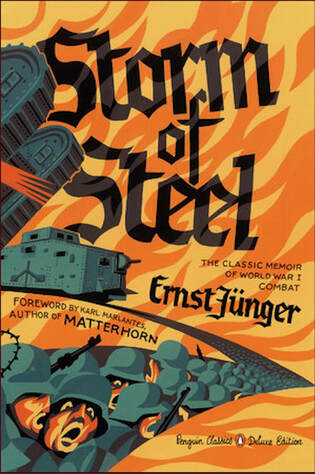

Ernst Jünger’s “Storm of Steel” (Penguin edition, 2004). Ernst Jünger’s “Storm of Steel” (Penguin edition, 2004). David Hoefer, of Louisville, is the co-editor of The Last Resort. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. The Last Resort is about young men in the final stages of youth, an all-too-brief period of camaraderie in the leafy, rural backdrop of Anderson County, Kentucky. But that’s not all John Goodlett’s book is about. Pud’s letters home while training to be an infantryman and later witnessing the closing days of World War II present another important part of his story. In the spring of 1945, he faced the desperate violence of Germany’s failing opposition, as well as the skeletonized horror of a newly liberated concentration camp. Evidence suggests that Pud was a good soldier if not exactly a natural one. In a letter from France dated 6 Feb 1945, he explains to his mother and sister that his life outdoors has prepared him well for living in muddy trenches and handling a rifle. Without doubt he was a successful soldier: he made it home alive, returning to civilian life. I’ve been reading another, more extensive war memoir of an altogether different character. The book’s English title is Storm of Steel, and its author is Ernst Jünger, a German veteran of trench combat in World War I. By all accounts, Jünger was a natural soldier—born to it and unashamed of the role he played in battle. At the same time, he was a gifted writer, who left us what many consider one of the best accounts of Western Front warfare, that four-year spectacle of death and obliteration. Storm of Steel is quite unlike the pacifist tracts and novels that were popular in the years following the war’s end. Rather, it is a sharply observant record of the day-to-day tedium, punctuated by chaotic, deafening menace, that defined the conflict, captured by Jünger without sentimentality or celebration. I bring this up because of a passage early in the book that caught my attention. New to his deployment, Jünger is experiencing shelling from a French position for the first time. His unit is posted by a woods that has yet to be destroyed by the fighting. Of this he writes: “Towards noon, the artillery fire increased to a kind of savage pounding dance. The flames lit around us incessantly. Black, white, and yellow clouds mingled…And all the time the curious, canary-like twittering of dozens of fuses. With their cut-out shapes, in which the trapped air produced a flute-like trill, they drifted over the long surf of explosions like ticking copper toy clocks or mechanical insects. The odd thing was that the little birds in the forest seemed quite untroubled by the myriad noises; they sat peaceably over the smoke in their battered boughs. In the short intervals of firing, we could hear them singing happily or ardently to one another, if anything even inspired or encouraged by the dreadful noise on all sides” (2004:27-8, trans. by Michael Hofmann). Nature abides; the birds carry on despite the groundswell of violence, without the ability to penetrate any realm beyond immediate circumstance. Observations like these reimagine war as a kind of stupid, background static. This passage made me think about Pud, who faced down his own difficulties in war. It recasts the contrast between a delight-filled ramble in the woods and a dangerous, cold night in a foxhole as a single, somewhat enigmatic incident. This compression of tranquility and anxiety, of blessedness and its withdrawal, summarizes the power that we also detect in John Goodlett’s journals and letters. A little further into Storm of Steel there’s a second passage that illustrates nature’s eternal return: “Rank weeds climb up and through barbed wire, symptomatic of a new and different type of flora taking on the fallow fields [between the front lines]. Wild flowers, of a sort that generally make only an occasional appearance in grain fields, dominate the scene; here and there even bushes and shrubs have taken hold. The paths too are overgrown, but easily identified by the presence on them of round-leaved plantains. Bird life thrives in such wilderness, partridges for instance, whose curious cries we often hear at night, or larks, whose choir starts up at first light over trenches” (ibid.:41). Ecological succession unfolds even in the most forbidding circumstances. Nature is that stubbornest of all habits. Storm of Steel is worth your time (though not without some gruesome moments). Jünger knew the fear of war but never the fear of writing about it. By giving us a polished but truthful account, he goes beyond the moralism that actually detracts from depictions of the Devil’s great gift to humanity.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed