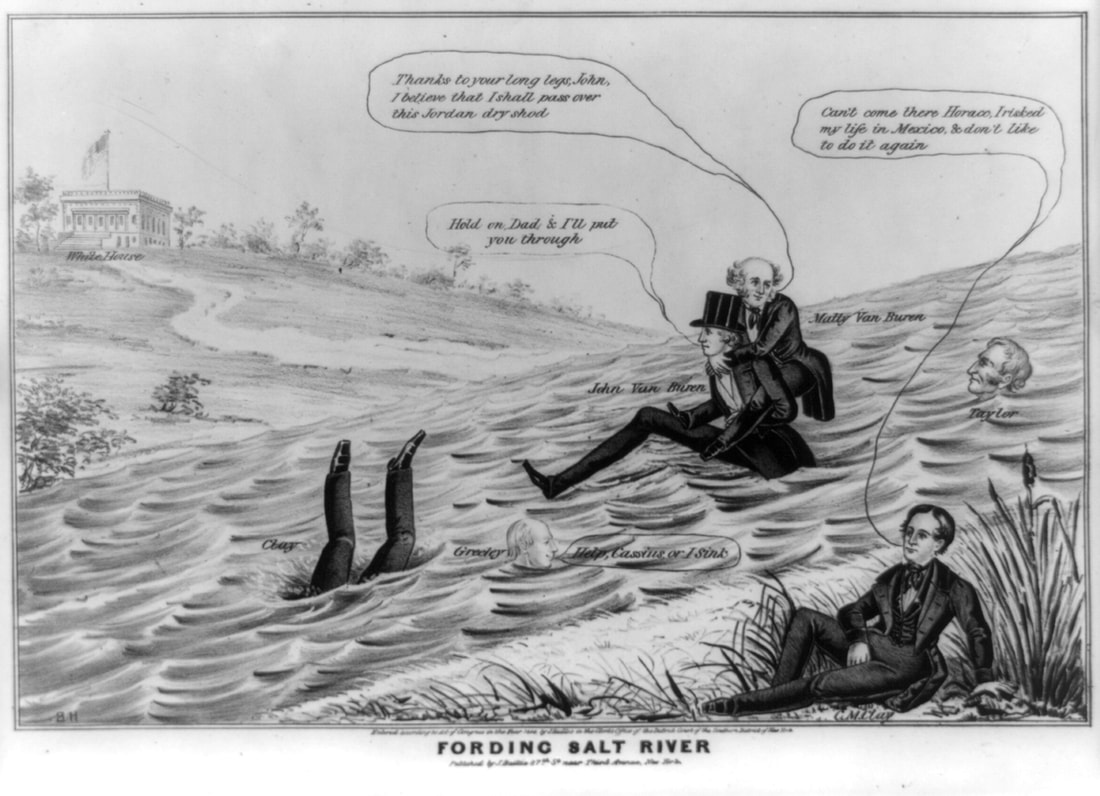

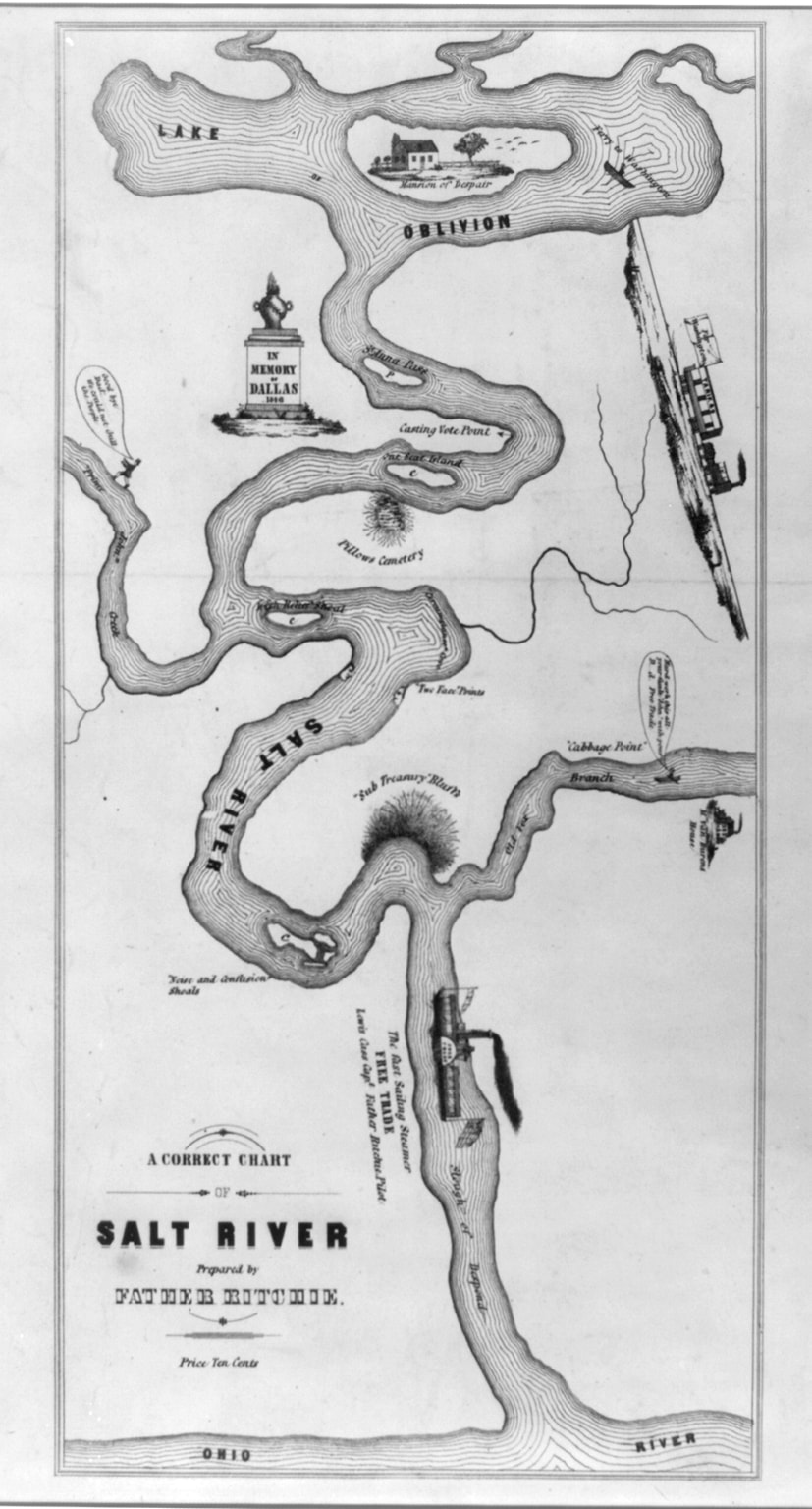

Salt River in Anderson County, about 50 miles east of Bullitt County. Note the downed tree and the rocky snag just upriver of the large boulders. (Photo by Rick Showalter) Salt River in Anderson County, about 50 miles east of Bullitt County. Note the downed tree and the rocky snag just upriver of the large boulders. (Photo by Rick Showalter) In addition to reveling in time spent camping and fishing along central Kentucky’s Salt River, Pud Goodlett was deeply interested in both politics and history. So I have to wonder if he was familiar with the nineteenth-century phrase “rowed up Salt River.” Clearing the Fog reader Liz Atchison passed along the tip about this expression, commonly used to describe a political candidate who finds himself in inhospitable waters, usually because of the machinations of a political adversary. With defeat nearly certain, the hoped for victory seems as impossible as successfully rowing up the shallow and rocky shoals of Salt River. As we wade deeply into the 2018 political season, it seems like a good time to bemuse ourselves with a colorful expression that reveals much about both our nation’s raucous political history and the central role that the unassuming Salt River played as a conduit for the unwieldy transportation of people and products to and from the mighty Ohio. In her blog, political historian Susan Barsey describes the “mythical” river as follows: “Salt River was, to begin with, a real place: a small, winding tributary of the Ohio River originating in the wilds of Kentucky. Before railroads, the Ohio was the main cross-country route for reaching the eastern cities. To go up Salt River was to leave a broad waterway, which steamboats plied daily carrying hundreds of passengers, and end up in the middle of nowhere on a dead-end stream.” (“The New Jeffersonian,” Mar 25, 2012) There appears to be some mystery about the origins of this expression of ignominious defeat. According to Charles Hartley of the Bullitt County History Museum in Shepherdsville, Ky., Franklin Pierce used the phrase in a letter dated 8 Oct 1831. Apocryphal stories tell of Henry Clay succumbing to the treachery of a Jackson Democrat who, in 1832, rowed Clay up Salt River rather than to a speaking engagement in Louisville. An 1848 political cartoon shows Zachary Taylor rowing his resigned opponent, Lewis Cass, up Salt River. Another shows Martin Van Buren being carried piggyback through the dangerous waters by his son, John, while Henry Clay plunges head-first under the water and Cassius Clay lounges out of harm’s way on the shore. Hartley cites several other possibilities for the origin of the phrase, including river pirates and a smart-mouthed local postmaster. In “Bullitt Memories: Getting Rowed Up Salt River,” he concludes that the phrase most likely came into usage in the 1790s when newspapers reported that local officials rowed a petty thief up the river to administer a punishment outside the jurisdiction of the town and perhaps outside the law. Pud never uses the phrase in his 1940s journal. Perhaps the expression had fallen out of favor by that time. Or perhaps the unsophisticated teens weren’t yet plotting the political doom of candidates they deemed loathsome. Unsurprisingly, Goodlett returns from the war in Europe with a more keenly developed political acumen. His 1950s journal makes it clear that the adult scholar would have been quick to name several politicians he would have liked to row up Salt River, if he only could have lured them to his boyhood haunt.

3 Comments

Joseph Ford

4/11/2018 12:10:05 am

As I began reading this entry, I had high hopes about the redemptive power of nature and river. Alas, the machinations of man too often bend them to his nefarious purpose!

Reply

Sallie Showalter

4/11/2018 08:15:55 am

I'm so lucky to have friends who can nudge me away from despair wrought by man's malicious enterprises and toward nature's restorative power! Thank you, Joe.

Reply

David Hoefer

4/14/2018 01:23:10 pm

A bit more historical flavor. Thomas Jefferson mentions Salt River in his Notes on the State of Virginia, published in 1787, when Kentucky was still a western extension of the Old Dominion. In his detailed response to Query 2, regarding navigable interior waterways, Jefferson writes, "Salt River is at all times navigable for loaded batteaux 70 or 80 miles. It is 80 yards wide at its mouth, and keeps that width to its fork, 25 miles above" (1787:11) – presumably a reference to the Rolling Fork. Batteaux were the flat-bottomed riverboats of the day. Since Salt River is about 150 miles in length, the passage suggests that, even at that early date, there was an inkling that the river might not always be conducive to overwater travel. Of course, whether Jefferson knew the river's actual length is debatable. For more: http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/jefferson/jefferson.html.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed